Welcome to the Minerals.net Newsletter

Welcome to the summer edition of the Minerals.net Newsletter. The hot and lazy summer days have put us behind a bit on updates, but we still do have plenty of news to share with you. Much of our audience, especially in the academic and educational circles, are off this time of the year. However, with September just around the corner, we're looking forward to activity picking up.

New Quartz/Chalcedony Gemstone Pages

Quartz represents the largest group of gemstones. Our gemstone pages were lacking content on many of the important Quartz varieties. Over the past couple of months we have been addressing this. We have added additional pages, complete with photos, on numerous Quartz and Chalcedony gemstones.

We created the following new Quartz gemstone detail pages:

We also entirely fixed up these existing Quartz gemstone pages:

For the Chalcedony gemstones, we created the following

new gemstone detail pages:

|

|

Many of our readers have asked us to include the chemical formula and crystal system on the gemstone detail pages. We initially created the pages without these fields, since we had thought this information was too detailed and was anyways included on the corresponding mineral pages. However, due to numerous comments from our web visitors, we have added these fields to all gemstone detail pages. We have also added a transparency field for all gemstones, as well as cleavage (which may be useful to gemstone cutters). |

We are working on making the Minerals.net Q&A the best location on the Web for people to post their mineral or gemstone related questions, and receive answers from the community. This is a great tool for both experts and students alike. Please share any questions you may have, and feel free to contribute answers.

answers.minerals.net |

The Endangered Mineral Deposits

It is a sad reality that the classic mineral localities are becoming relics of the past. Many of the amazing mineral deposits across the world have closed permanently, or have been shut to collectors. Hardly any of the classic exceptional mineral deposits are still producing collectible specimens. It is a sad reality that the classic mineral localities are becoming relics of the past. Many of the amazing mineral deposits across the world have closed permanently, or have been shut to collectors. Hardly any of the classic exceptional mineral deposits are still producing collectible specimens.

This often happens when a mine becomes exhausted of its ores, where there remains no economic viability in keeping it open. A more acute factor behind important mines closing is that the bulk of ore production in the United States or other developed nations is shifting overseas, where labor laws are more lax and production costs significantly cheaper. This forces the closure of the mining operation, and in addition to ensuring that no new specimens are extracted, in many cases the mines are permanently filled or sealed. Ocassionally the old mine dumps provide relics of the past, but these often get picked through without any new supply.

The large mining operations, such as traprock or limestone open pit quarries, are beehives of activity where mining operators often prohibit the interfering of collectors. Aside from organized field trips by clubs, and those few stealth collectors who enter illegally after hours, many of these quarries are unable to produce minerals due to collection restrictions. Though some mines allow exceptions, or their owners appreciate specimen collector value, most are clearly not interested in specimen preservation. This results in vast amounts of quality specimens ending up in the crusher. This has to do both with industrial apathy towards the collectible nature of minerals, as well as fears of insurance liability should a collector get injured and sue. The large mining operations, such as traprock or limestone open pit quarries, are beehives of activity where mining operators often prohibit the interfering of collectors. Aside from organized field trips by clubs, and those few stealth collectors who enter illegally after hours, many of these quarries are unable to produce minerals due to collection restrictions. Though some mines allow exceptions, or their owners appreciate specimen collector value, most are clearly not interested in specimen preservation. This results in vast amounts of quality specimens ending up in the crusher. This has to do both with industrial apathy towards the collectible nature of minerals, as well as fears of insurance liability should a collector get injured and sue.

Some of the famous deposits are worked solely for collectible specimens. However, access to these types of mines is generally restricted to the mine workers and staff, with occasional VIP visitors. Such mines are not open to the general public. This was the case of the Sweet Home Mine in Colorado which produced the finest Rhodochrosite crystals. It was originally worked as a silver mine, and then closed down. The mine was reopened by a large mineral company solely to produce the outstanding Rhodochrosite specimens. This company took sole mining rights of the mine, and it was not open to the public.

Some closed mining localities have been transformed into museums. Such is the case of the famous Franklin and Sterling Hill mineral deposits in New Jersey. These mines were former productive zinc mines, but due to the rising costs of production and increased competition among overseas producers, both these mines were forced to close. After their closure they were transformed into museums with guided tours, and. Collecting can still be done in their old dumps which occasionally still produce specimens of interest (although nothing like the old days during active mining operations.)

Some closed mining localities have been transformed into museums. Such is the case of the famous Franklin and Sterling Hill mineral deposits in New Jersey. These mines were former productive zinc mines, but due to the rising costs of production and increased competition among overseas producers, both these mines were forced to close. After their closure they were transformed into museums with guided tours, and. Collecting can still be done in their old dumps which occasionally still produce specimens of interest (although nothing like the old days during active mining operations.)

Much new material on the market has been coming from developing countries. There has been a recent unprecedented surge of minerals originating out of Russia, China, and Madagascar, with new deposits continuously being discovered and worked in these places. Often, specimen mining rights are obtained by a company or individual mineral collectors who pay for the privilege to collect and sell their finds to the dealers. These end up making their way to all the major shows and flooding the market.

The problem with this new material is that its mass production stifles appeal. For example, when the gorgeous Cuprites started coming out of the Rubtsovskoe Mine in Russia, these were grabbed by collectors. However, now over two years after the discovery, this material is so abundantly available, and can be found by many dealers at any given show. This mass availability indeed waters down its collectible appeal.

Our hope is that public awareness will increase among mine owners worldwide so that they be more open towards specimen preservation. It is truly a shame when quarries with outstanding potential just send their treasures to the crusher, forever losing those minerals it could have produced. While some active mines do have a responsible conscientiousness, many unfortunately do not. So aside for those lucky road cut or construction discoveries, it is becoming increasingly difficult for the casual collector to find good locations to effectively dig for minerals. |

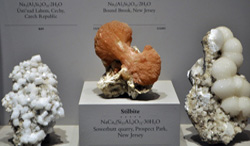

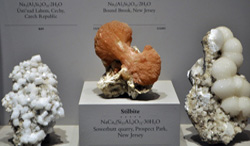

The Smithsonian Gem and Mineral Hall

I recently had the oppurtunity to visit the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. The Smithsonian contains one of the most significant collections of minerals and gemstones in the world, and everything is clearly labeled and well-organized. The only downside to visiting in the summer is the volume of people, which can make it difficult to properly view the collection. I was amazed at the wall of people surrounding the famous Hope Diamond, with people literally waiting on line to get a glimpse of it inside its rotating case. This museum is a must-see for all visitors to the Washington area, and I encourage all those interested in mineral and gemstones to plan a visit.

-Hershel Friedman

|

Give us Feedback!

We appreciate feedback! Please email us with any comments or suggestions, and any errors or bugs you may find. To contact us, please visit our Contact page. |

Copyright 2012 H. Friedman | Minerals.net, all rights reserved. |

It is a sad reality that the classic mineral localities are becoming relics of the past. Many of the amazing mineral deposits across the world have closed permanently, or have been shut to collectors. Hardly any of the classic exceptional mineral deposits are still producing collectible specimens.

It is a sad reality that the classic mineral localities are becoming relics of the past. Many of the amazing mineral deposits across the world have closed permanently, or have been shut to collectors. Hardly any of the classic exceptional mineral deposits are still producing collectible specimens. The large mining operations, such as traprock or limestone open pit quarries, are beehives of activity where mining operators often prohibit the interfering of collectors. Aside from organized field trips by clubs, and those few stealth collectors who enter illegally after hours, many of these quarries are unable to produce minerals due to collection restrictions. Though some mines allow exceptions, or their owners appreciate specimen collector value, most are clearly not interested in specimen preservation. This results in vast amounts of quality specimens ending up in the crusher. This has to do both with industrial apathy towards the collectible nature of minerals, as well as fears of insurance liability should a collector get injured and sue.

The large mining operations, such as traprock or limestone open pit quarries, are beehives of activity where mining operators often prohibit the interfering of collectors. Aside from organized field trips by clubs, and those few stealth collectors who enter illegally after hours, many of these quarries are unable to produce minerals due to collection restrictions. Though some mines allow exceptions, or their owners appreciate specimen collector value, most are clearly not interested in specimen preservation. This results in vast amounts of quality specimens ending up in the crusher. This has to do both with industrial apathy towards the collectible nature of minerals, as well as fears of insurance liability should a collector get injured and sue. Some closed mining localities have been transformed into museums. Such is the case of the famous Franklin and Sterling Hill mineral deposits in New Jersey. These mines were former productive zinc mines, but due to the rising costs of production and increased competition among overseas producers, both these mines were forced to close. After their closure they were transformed into museums with guided tours, and. Collecting can still be done in their old dumps which occasionally still produce specimens of interest (although nothing like the old days during active mining operations.)

Some closed mining localities have been transformed into museums. Such is the case of the famous Franklin and Sterling Hill mineral deposits in New Jersey. These mines were former productive zinc mines, but due to the rising costs of production and increased competition among overseas producers, both these mines were forced to close. After their closure they were transformed into museums with guided tours, and. Collecting can still be done in their old dumps which occasionally still produce specimens of interest (although nothing like the old days during active mining operations.)